(Interview via Creative Independent)

Musician Kristin Hayter, best known as Lingua Ignota, on how her music and live performances help her exorcize trauma, reframing genre tropes to create something entirely new, and what she got out of art school.

How would you describe your artistic philosophy?

I think that my work is often about dismantling different systems and looking at the inner workings of different systems. I often take kind of disparate systems or different ways of coding or different kinds of language, and I’ll put them together and try to alchemize them into something new. This has been part of my practice for over a decade—taking different things, different disciplines, different languages, and trying to create something new and strange out of that.

I think that the philosophy is based in juxtaposition and trying to create something new out of pre-existing modes. I guess it’s a postmodern way of looking at things, just kind of deconstructing previously existing things and then trying to make something new.

“Postmodern” is one of the first terms that would spring to mind when I think of your work. What about that process appeals to you? Why not just make genre music?

I think I’m interested in things beyond what already exists, and I don’t want to make anything that has already been made. But at the same time, I want to use methods that have been proven effective to make something new, and I feel like staying within any one thing or confining myself to any one mode of making things—any one discipline or genre or style or process—is just limiting. I feel like making things should be kind of unlimited.

One can hear all kinds of different styles in your music—noise, classical, even church music. Is there a method with which you piece these styles together, or is it just a matter of whatever seems to work?

I do often have ideas of how I want to layer things or what’s going to go where. It’s all very carefully wrought, generally. Sometimes it is more experimental or just throwing things together and seeing if they work, but generally I try to utilize the context of a genre or a trope. For instance, in noise, a thing that often happens at the end of the set is, I call it “harsh to kill switch,” which is you just end the set without any warning. You just turn everything off and it’s just kind of shocking or a very disorienting moment where everything kind of falls away very quickly. But I like to put that within the context of a different genre or a different style or a different moment. So I like to take things that I think are effective in different genres and accumulate them and have them as sort of a vocabulary that I can cull from.

When I went to school at the Art Institute of Chicago, that was kind of how I was taught to make art. Not so much about refining the craft, but how to think about how art should be made. So I always think about what this particular moment needs to say, and what is the best way to say what needs to be said.

Beyond that, what are the most important things you got out of art school—specifically theories or methods that you apply to Lingua Ignota?

I think that my time at the Art Institute was probably the most valuable time that I’ve had in any kind of pedagogical environment. I learned how to think about art, and I also became very invested in art history, and that was actually one thing that I wanted to go on and study in a Master’s program or a graduate program. I’ve always been very interested in the conceits and vernaculars of different styles, so I was always looking at what defines Impressionism versus Expressionism versus Abstract Expressionism—which are all very different—but at the same time, I really enjoyed that categorization. So I think looking at art history and looking at things that had existed previously and how those things are defined really influenced how I choose to not define my work, or how I choose to somehow re-navigate categorization and genre and style.

I also got a bunch of crap out of my system in art school. Me and everyone else there were all a bunch of entitled white kids who all thought we were geniuses, so they teach us about the great works of the 20th century and great performance art and whatnot, and then everyone wants to make the most offensive, shocking thing possible. And I made the worst stuff. My first year in art school, I just made the worst, most offensive fucking trash that I would be so horrified by today. But I think me and a bunch of other kids kind of got that out of the way, and that’s been helpful for making stuff now, or looking at what, historically, we think of as controversial or bad or shocking, and figuring out ways to re-navigate that as well.

Speaking of deliberately provocative work: Your last record was called All Bitches Die. Can you talk about that in relation to your art school stuff that you called “trash,” but then realizing at some point, “Well, a little bit of this attitude can be useful”?

Right, yeah. The language around All Bitches Die, and the stuff previous to that, is directly indebted to, or is appropriated from, other ideologies that are technically offensive. They’re indebted to an appropriator from misogyny, and from the misogyny of extreme music in particular. So I think, as far as making something controversial and the weight of that, or the value of that, and what it can and can’t do… it seems like it’s a matter of self-awareness and intent. When I was making total trash when I was 18 years old, I thought it was the greatest thing ever, and I thought it was super cool to make a short film that’s just people getting blowjobs over one of Tchaikovsky’s piano concertos and then slow motion videos of someone receiving the Eucharist or something. It’s just like, “Oh my god.”

But [with All Bitches Die], I’m aware of the absurdity of the language, and I’m aware of the absurdity of the imagery, and I’m looking at these very specific tropes in extreme music, and the Satanic posturing, the super dark posturing, and I’m taking that and trying to claim it in a different way. And there are some people who think that I am just trying to shock everyone or make something controversial, but what I’m really trying to do is take all of this stuff that I feel is both very loaded and very much meant to be like a weapon, but also is kind of meaningless because it’s just the genre signifiers. So yeah, people are giving me shit right now about my titles, and I’m like, “Look at your titles! Your titles are exactly the same thing, just in a slightly different context, and I’m deliberately taking from that world.” So for me, it’s a matter of intent and reframing.

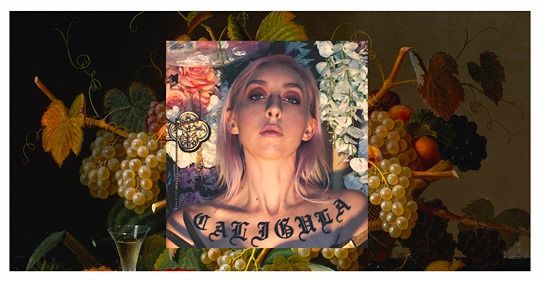

Your new record, Caligula, has a bunch of guest musicians on it. What do you see as the value of collaboration versus creating alone?

With the previous records, I was completely alone. They were recorded in complete isolation. All Bitches Die was recorded literally in a shed in the woods in Rhode Island, where I lived and was very miserable for a long time. And Caligula was about a very specific time in Rhode Island where I felt kind of abandoned and invalidated by my community. Caligula, at its root, is about that. It’s about speaking out about abuse in Providence. It’s very much like an onion with many layers, and it has many micro and macro layers to it about social context and then interpersonal context, but ultimately that’s where it stems from.

I felt so alone when I was making this music, but I wanted to have people close to me. I wanted to have protection on the record. It’s a very strange thing. But some of my really good friends—Mike Berdan, Noraa Kaplan, Lee Buford, and Sam McKinlay—were very much there for me at that time when I was going through hard stuff, and to have them on the record was really important to me. It felt like having my community there, my close circle of trust. So for this record, that’s why they’re there.

I am a little bit tyrannical, as far as control, though. I have to do everything myself and I have to have total autonomy over the work in the end. So the collaborations were really more about the presence, and also the fact that these people are super talented and I admire their talents, but I wanted to have them close to me.

From what I can gather, Caligula is more political than All Bitches Die. As someone who has a platform and an audience, do you feel a sense of responsibility to talk about what’s going on in the world around us—even if it’s just metaphorically?

I do, and I feel like I fail at it. I feel like I’m not doing enough. I feel like I can’t do enough. I think I don’t know what to do about that. I don’t know how to be a good advocate, or how to move things forward. I only am an artist, and I don’t have a background in activism, per se, or political theory. I try to be educated as much as I can, but I also don’t know where my role ends and starts.

I have a lot of people write to me, personally, almost every day, telling me about their personal experiences, and a lot of times I get people writing to me about their experiences of abuse by somebody whose music I just posted about, or something like that. It happens almost everyday. And I don’t know what to do. I don’t know how to help people in the best possible way. So I’m currently trying to figure out how to navigate that. I want to help, I just… I can barely process my own stuff, and so to be responsible for other people… I try to help, and I often try to do harm reduction, but I don’t like to post about it or talk about it, necessarily, and try to handle things privately among the people involved. But it is kind of like a constant thing in my life that people approach me and want me to help them through some sort of situation. So I’m trying to figure out how to help the best I can, but also recognize my own limits.

You donated the proceeds from your first EP to the National Network to End Domestic Violence. That seems like a pretty good start, as far as helping goes.

Yeah, that’s one thing, but I feel like I can do so much more, and I feel obligated to do so much more. But I do also feel that people in times like these do have different roles, and if you have the resources to give money, then you should give money. If you don’t have the resources to give money, then there’s something else you can do. Or if you are not able to go out and be boots-on-the-ground or be in the streets protesting, there is another way to do good in the world. Sometimes I feel like people think that their way of doing things is the only right way, but I think that there are a bunch of different ways to go about doing right in the world, and I just feel like I don’t do enough. I don’t know.

To what extent do you see music and art, in particular Lingua Ignota, as important or even necessary for processing anger, pain, or trauma?

For me, it’s been the only way I have processed trauma. I kind of don’t believe in traditional systems of healing that we have in place for trauma, or for really anything. I found that those systems don’t work for me at this point. Maybe they will in the future. So creating this music and putting it in the world has been my only way of finding accountability, first of all, or trying to draw out accountability, or drawing attention to things that have been swept under the rug or invalidated or neglected, and then being able to express this anger and the despair and the hopelessness and all the other boiling feelings. This has been the only way that I’ve been able to effectively exorcize them.

You used some text from the Jonestown tape on Caligula. Did you have any reservations about that? It’s one thing to take your own personal trauma and make art with it—that’s obviously your prerogative—but did you have any misgivings about using the trauma of others?

I do think about that, and I also thought about that a lot when I had Aileen Wuornos in my work often. I thought about what it means to co-opt someone’s pain and if that was the wrong way to go about it or if I should’ve just stuck to my own story. Ultimately with Aileen, I thought about including her in the work as a way to honor her and as a way to bring respect and a sense of dignity to her story, which so many people don’t really know about, or just know about from watching the film Monster with Charlize Theron.

Thinking about utilizing or having the text to, “If the poison won’t take you, my dogs will” being not exactly from Jim Jones, but kind of paraphrasing the death tapes a little bit, I did think about the people involved, that it was an actual tragedy. But I was mostly concerned about the attitude of Jim Jones himself, and looking at this super manipulative language, and putting that into the context of survivor-hood and manipulation and interpersonal relationships, and then also as just this horrifying fantasy that I have that the only way to end my trauma is to kill myself. So that’s really what the song was about, and I hope that nobody feels harmed by that, or by the use of that text—specifically nobody related to that massacre and that tragedy. But if they do, I’ll try to be accountable for it.

On Caligula, you also address some of the social media commentary on your work. Why did you want to do that? Why did you choose to respond rather than stay above the fray?

I think that we live in a really bizarre time, and I think that with social media and the internet, I would be remiss to not explore that if I wanted to make truly contemporary work. I am really interested in the boundary—and this plays out in my live shows as well—I’m interested in challenging the demarcation between the audience and the performer, the audience and the artist, the listener and the musician, and really looking at those relationships and flipping them around or shifting perspective, shifting gaze. Sometimes in the work, it’s kind of unclear who’s being looked at or who is being listened to. I am interested in what people have to say about the music, because I think it’s very strange music, so looking at comments that people might have that may be invalidating of the experience or of the work and taking that and flipping it again… the relationship between myself and the listener is very interesting to me.

On that note, do you write with your audience in mind?

Sort of, but not really. First and foremost, it has to feel like something I’m compelled to do, or like it’s necessary in some way for the thing to be in the world, and that comes exclusively from a need from me. I think that if no one ever heard the work, it wouldn’t matter, ultimately, to me. I mean, with my previous couple of records, I honestly didn’t think anyone would hear them. But with this one, I knew that people were paying attention, and so there are some things on this record that kind of directly reference that, and there is an awareness of the audience in the music. But I don’t think I necessarily write for them. I think it’s just that they’re kind of in the periphery—or the gaze shifts to them at some point.

Earlier you mentioned your live shows, which are very physical. You’ve even given yourself a concussion onstage. The need to go all out, even at your own peril—where did that come from?

It’s kind of a problem, to be honest. [Laughs] I think it very much has to do with my history of trauma, and that, for me, I don’t really feel that much unless I’m in a legitimately kind of dangerous place. So I actively seek dangerous situations, and I think it’s really important to me to bring a level of authenticity to what I do and to bring actual honesty and an actual… like, I can’t be pretending to hurt myself. I can’t be pretending that the work is about pretend violence. The work is about violence and I am hurting myself, and that feels like a direct comment on the posturing of a lot of music—the fake blood and the costumes and stuff—and creating something truly terrifying that’s just kind of corporeal instead.