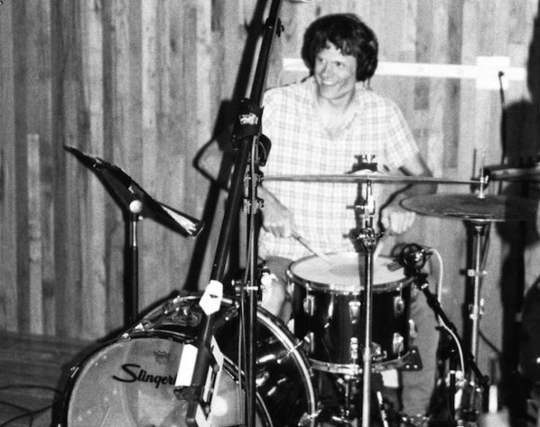

On its self-titled debut, released this past May 5, the indie-rock collective Big Walnuts Yonder fuses wild time shifts, explosive punk tones, and unhinged improvisation on ten electrified, cohesive tracks. The veteran group, comprising bassist and vocalist Mike Watt (Minutemen, the Stooges), guitarist Nels Cline (Wilco, Nels Cline Singers), guitarist and vocalist Nick Reinhart (Tera Melos), and drummer Greg Saunier (Deerhof), loaded their debut with frenetic chops, free-jazz-influenced ventures, and sharp, daring moments. Modern Drummer asked Saunier about the recording process, the album’s metric twists, and more.

MD: What was the recording process like on Big Walnuts Yonder? The session sounded fairly spontaneous. How did you approach that situation?

Greg: When you’re in a recording studio and somebody’s footing the bill and time is tight, then, yeah, it feels a bit like someone’s saying, “You’d better show us some results quickly,” which can sort of feel spontaneous. And spontaneity is a funny thing. Ironically, sometimes I feel it most when a band has rehearsed something like crazy and can take any kind of crazy risks with the performance. Big Walnuts Yonder wasn’t like that, though. When Watt puts fingers to bass, there’s kind of nothing you can do—he lays down the law. I don’t know, maybe he feels the same way about me! We both can be really pushy players when the spirit hits. And we both tend to rush a lot. We’d been planning this meet-up for years, so once we were finally all in the same room, it was just relentless, frantic energy.

MD: The drum parts on the record have a great way of recalling influential eras in music, rather than specific drummers from those eras. Who are your influences? And were you trying to take any of their concepts into this record?

Greg: In my band Deerhoof, we tour a lot and we can get pretty loose because we’re so familiar with the songs and each other. I often think my main influence is Keith Richards, even though he plays guitar. His style is so carefree and unpredictable. He might play ahead of the beat or behind, do some unexpected syncopation, or just stop playing altogether and smoke a cigarette for a couple bars. But in Big Walnuts Yonder, I had to be way more Charlie Watts than Keith Richards. There’s that line in “Jig-saw Puzzle” on Beggar’s Banquet: “And the drummer, he’s so shattered, trying to keep on time.” It’s of course a beautiful description of Charlie’s role in the band.

MD: In “All Against All,” it sounds like the band modulates the tempo from the first to second section based off of the first section’s quarter-note triplet. Could you explain some of this song’s time changes?

Greg: Funny you should pick that one—that’s the one song I brought in to the gang. And yes, it’s a metric modulation. I think shifting to a tempo related by a triplet can feel so cool and refreshing. Of course, if you think the timing is funny now, you should’ve heard my demo. I did it in GarageBand, [and] if you have RAM issues, then there’s latency, and the timing shifts around. When the guys heard the demo right before the session, I think they got pretty worried that they picked a drummer who didn’t understand rhythm!”

MD: The tempo changes create somewhat of a jarring effect. Was there any concept you were going for?

Greg: I guess the concept is “non-development,” à la Stravinsky, Picasso, or Kubrick. It was Watt’s idea to put that track first on the record, and I was very flattered by that because having that abrupt change-of-mind right at the beginning of the record is even more jarring. I loved the way Kurt Cobain started In Utero with, “Teenage angst has paid off well, now I’m bored and old,” and then completely changed the subject for the rest of the song.

MD: How did you approach the drumming on “Flare Star Phantom,” and how would you take a freer approach to drumming in general?

Greg: That’s Nels’ song, and I thought it was beautiful so I just went for it. But if you saw how intense Nels, Nick, and Watt were going at it on that song, you would know that the drummer was really anything but free. I had to go as full-blast as I could without letting up for more than maybe half of a second. Playing out of tempo is also not really freedom either, because you’re restricted from playing in tempo.

I play free improv with people all the time, even with Nels. And in free improv anything might happen, including playing quietly or playing a beat. I don’t know how to describe my approach to free playing. When it comes down to it, it’s no different from any other playing. Maybe it has something to do with constantly taking the temperature of the room and trying to be sensitive and bold at the same time. I want everyone to have more fun than a barrel of monkeys.

MD: The drums sound great on the record, and the tones seem like they vary from song to song. What went into getting the drum sounds for the album?

Greg: Thanks! I mixed the whole record myself, at home. I got used to doing that with Deerhoof, and I love it because it means you can take your time. So I did take my time, which is why this record came out two years after we recorded it. I’d make mixes of everything and get burned out, drop it for a month, and come back and start over from scratch with a new approach. After several rounds of that you’ve got some different-sounding mixes to choose from.

MD: What drum setup were you using on the record?

Greg: I used a kick, snare, hi-hat, and cymbal setup. Tony [Maimone, producer] put way more mics on me than I had pieces in the kit. The kick was un-muffled and tuned really high, especially on the batter side. I used two 18″ ride cymbals for hi-hats. The top cymbal was a flat ride with a huge crack in it, and it made almost no sound no matter how hard I played. I learned that trick from playing many years in a loud band with a quiet singer who gives you dirty looks if your cymbals are too loud.

MD: Is there anything you’ve learned from producing and mixing records that has changed your drumming perspective?

Greg: You’d think so! But in the moment of making music, all bets are off. It’s all about the human interaction.

Via Modern Drummer